Introduction

This post is about my relationship to my hobby: Making music. This post is also about societal pressures and how these pressures can ruin things we hold dear. This post is also about a Casio keyboard. This post is about productivity and how it can damage us.

“Efficiency” is the name of the game in our modern society and we have been caught in its trap. The need for value maximization that we feel in our daily lives is far-reaching and can be all-encompassing. I have been caught in this trap and it has almost ruined my favorite hobby for me. This is the story of how I came to this realization.

A Story of Music-Making

Back when I was studying computer science in Munich, I developed an interest in making music. This is a brief summary of how I developed a love for my favorite hobby and how that love, at some point, turned into bitter guilt.

Happy Salad Days

I had been playing the guitar and making silly songs on my computer since I was about 12, but I never seriously tried to write, record, produce, mix and master actual songs. Making music seemed like a completely impenetrable mystery to me, being both an artistic and engineering discipline. Going from a blank page, an empty tape, a room devoid of life and after a bit of writing, a bit of recording and countless hours of practicing in private to then present the listener with… something! Actual music, that delights and even moves people. How would anyone even go about starting such a process? It seemed magical to me, so I never tried in earnest.

When I moved to a new city to study, I didn’t take my guitars with me as there wasn’t space for them. Right then and there, music simply died for me. I wasn’t playing instruments, recording anything or even vaguely engaging in creative activity. It was all about visiting lectures, doing exercises, preparing for exams and so on, without really engaging in meaningful hobbies or even “fun” activities. As you can imagine, that’s not a good way to spend your life and I should soon find out.

After about two semesters, I was at a breaking point. Studying gave me no joy anymore and I failed to see the point in all of it. All optimism, promises to follow through and the energy to focus on complicated and complex topics were gone. I was caught in a toxic rut. My mental health was suffering and I needed a way to counteract; to fight back.

It was then that I listened to “Salad Days” by Mac DeMarco, and while it might seem corny, that song (and the whole album for that matter) changed something in me.1 The laid-back attitude the songs portrayed, the general feeling of being happy with what you have and the simple “Hakuna Matata”-esque message resonated deeply with me and gave me a new outlook on how to handle my whole life in a way. Through the power of YouTube’s recommendation algorithms, I then watched a documentary on DeMarco that goes into his music production process. Watching it made me do a double-take. “Wait a minute!”, I yelled in disillusionment, “This isn’t an impenetrable mystery after all!”. Watching him messing about in his studio seemed, more or less, like the stuff I was doing when playing around with my guitar. I could actually do that! The veil was lifted from my eyes and I dared, Audacity installed and USB microphone in hand, to start making music.

Learning Flow Ebbs

Of course, music production is a complicated affair. Doing it professionally is hard to do. It takes many years of experience to be efficient at recording, mixing and mastering. However, when you’re just recording songs in the comfort of your own home and the audience of those songs is mostly yourself, quality is not as important. The production doesn’t have to be flashy or incredibly well done. Creative activities are fun on their own. The byproduct of these activities is just a nice little bonus. Right?

When I started making music, most of my time was spent learning. Learning how to write songs, how to structure a creative process, how to record, how to mix, how to master. It was exhilarating and intoxicating. Every single time I learned something new, I could immediately apply it to whatever song I was trying to make at the time. An incredibly sweet spiral formed. I was losing myself to the pure joy of creating and experimenting. Finally, at last, I had found an outlet and the study-life balance I was looking for.

At some point, however, this stopped and for a very long time, I could not understand why. Even though my music-making efforts were productive, the fun and joy were somehow gone. Why? What changed?

I want to use the next section to analyze my behavior and attitude toward my hobby to make a larger point. Bare with me for a second.

Automation in Music

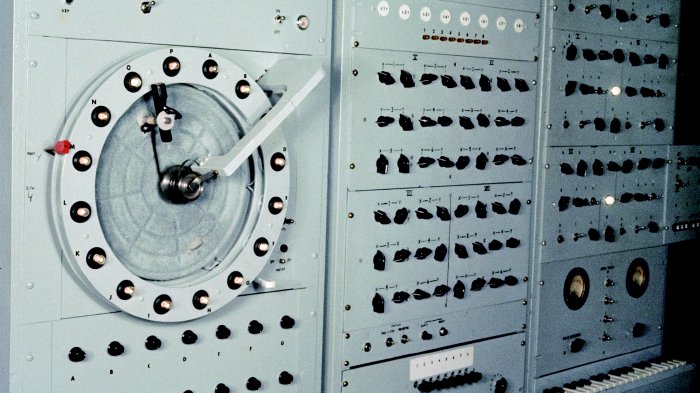

Since we have the technical means, music seemingly had an element of automation to it. Be it player pianos or fairground organs that perform pre-recorded music live or electro-mechanical sequencers that can be used to control other electro-mechanical devices to make music without actually playing instruments. One very early example of such a sequencer is the “Circle Machine” by inventor and composer Raymond Scott.

This industrial-looking device, which was just one of many inventions by Scott, uses light bulbs arranged in a circle and a photocell being moved over them to create a sequence of 16 adjustable pitches. In a lecture at the Advertising Age Creative Workshop in Chicago in 1962 Scott himself talked about the machine and demonstrated sounds that it can produce. One of the sounds the machine could be used to create was “[…] a sound to go with the sequence in a TV spot in which a storage battery is dying because the electrolyte is rapidly evaporating, ending in a short circuit”.2

Sadly, I cannot find concrete sound examples of the machine. The next best thing the internet provided me with is a modern reimagining of the Circle Machine by David Brown. While it is not an accurate recreation of the original, it fuels the imagination with ideas of what “wide range of unearthly sounds” (as Irwin Chusid and Jeff Winner put it3) the original was capable of.

Raymond Scott was not just an inventor but a jazz composer and an electronic music pioneer. His composition “Powerhouse” is featured in countless cartoons and his electronic works such as “Portofino” or the wonderful “Soothing Sounds for Baby” albums are a testament to his love of experimentation.4

Scott’s invention is a tool first and foremost. It allows for the creation of sounds that otherwise might not have been possible. The core idea of sequencing, the automated playing of notes, was later incorporated by many different synthesizer designers to allow players to program notes and then have them played back later in a perfectly timed fashion.

Since the introduction of the MIDI protocol, the automation of synthesizers and other musical devices has become much simpler. Digital signals are sent from machine to machine to make them play notes or control the parameters of their sounds. While this initially mainly served as a much-needed standardization in the music world, it has carried over into the modern world, as we are still using the exact same protocol in our digital audio workstations to control hardware and software.

Modern computer technology makes it shockingly easy to create music. Not only can we use the computer to quickly record, re-record, delete and edit sounds, but also to compose using manual or generative methods. The greatest thing about it is that you essentially don’t even need to buy actual instruments anymore.

Sampling and Software Instruments

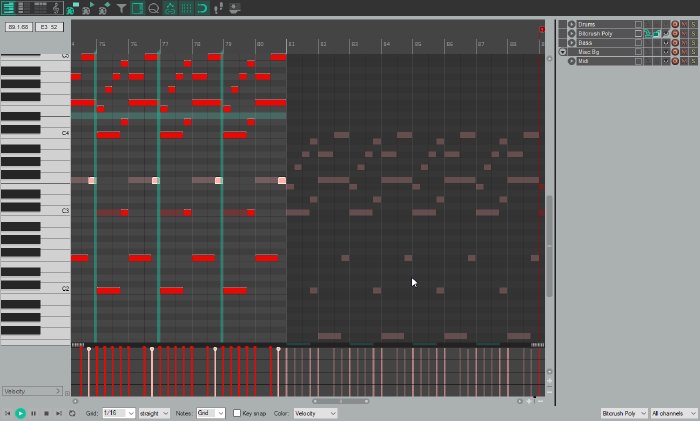

Today, music production has a workflow that is far removed from the electronic contraptions by Scott. We don’t have to build instruments to compose anything. In fact, we don’t even have to play instruments to make music. As was mentioned before, MIDI is still used in modern DAWs (digital audio workstations), like Reaper. Many DAWs feature a piano roll that makes it easy to program melodies and harmonies visually.

This allows the user to precisely define notes that should be played at any point in the composition, which also includes information on velocity or other characteristics of the performance. Using a MIDI keyboard, the notes can also be recorded “live” from an actual keyboard and then played back on different instruments, which can be actual hardware instruments that accept MIDI signals. The much more convenient and more often used option, however, is the usage of virtual instruments.

Why would anyone spend time on the arduous task of setting up real synthesizers and effects to record something, when you can simply load software into your DAW that will then be played using the MIDI information that is already in your project? Swapping out instruments and effects, for which all settings are automatically saved, can be done in seconds, going from an 80s synth to an orchestra to a church organ. We can even make multiple instruments play the exact same notes at the exact same time. The possibilities, when staying “in the box” are endless.5

Virtual instruments are not restricted to digital synthesizers and digital recreations of analog synthesizers. Using software samplers like Kontakt or Spitfire Audio’s offering you can essentially get any instruments you want for your compositions for cheap. Why pay a few hundred bucks for a real mandolin if you can buy a sample pack for a fraction of the price? In fact, why even assemble a band of folk-instrument playing folk for your folk music, when you can simply buy a digital folk-band recreation? No need to transport instruments or hire anybody to play for you. Such a hassle is left in the past. Instead, we lose ourselves in the intricacies of our piano rolls when trying to emulate real instruments as best as we can, trying to meticulously craft the perfect imitation of the real thing. In the end, it is quicker, more efficient and helps us to get the job done.

Better, Faster, Stronger

When I started making music I used Audacity and mostly recorded vocals and guitar using a cheap microphone. That was a pretty simple, but ineffective, setup. Audacity is a very good audio editor, but it isn’t tailor-made for music production. While it was fun to throw little demos together I quickly moved to Reaper as my software of choice.

With a quickly evolving library of software instruments, samplers and effects, a simple and productive workflow formed. I mostly wrote my songs on the guitar and used a MIDI keyboard to add layers to my compositions. Since almost everything happened inside my DAW, I was able to work on many projects at the same time. Switching from one song to another had minimal overhead, since I did not have to change my actual setup. My first big project was the album “The Life of Henry Darger” when I tried to chronicle the life of an outsider artist in musical form. In its production, I increasingly used more and more software to achieve higher and higher productivity. The time for experimenting was gone, there was work to do!

It felt important to me, that I was able to quickly work on songs. I had ideas in my head and I wanted to record and realize them immediately. Working with instruments in the real world seemed to be holding me down, which is why I shifted more and more toward automation and software. After all, software is also much cheaper than hardware, so there was no reason for instruments to bog me down.

Sudden Loss of Joy

After finishing the album, I wanted to do an even bigger project and began working on a huge concept album, with a planned runtime of two hours, which in the end I did not finish. I was left with 1227 files in 56 project directories, mostly unfinished demos, ideas, sketches and some songs, which then eventually found completion or some re-use. From some of these projects, I eventually made two EPs: One focusing on electronic compositions and another focusing on the themes of the original concept album. The second one was mostly written and composed during the COVID-19 pandemic. To switch things up, I used more real instruments (guitar, bass, synthesizer) this time but still relied heavily on software to flesh out my production. I wasn’t ready to buy a real Vox Continental organ but using a software clone, was fine by me.

After finishing my studies I wanted to take my hobby even more seriously than I did before. I moved to a new city and made plans how to set up a small studio in my new apartment. What microphones I would need to always have my guitar amplifier set up for recording, what software I would need to better produce my music and what other equipment might be necessary to achieve maximum throughput. I thought about getting some hardware synthesizers, which I had always dreamt of since listening to Pink Floyd at a young age, but I quickly eschewed these thoughts, as there were software alternatives, with more features and, first and foremost, more convenience.

As I was getting ready to make music again, something was off. I sat in front of my computer as always, MIDI keyboard at my side, hammering away at the keys, recording demos; and most importantly, doing it at highly optimized efficiency. Even though I created sounds I liked and composed works that I was sure I could develop into larger pieces, the joy I once felt was entirely gone. There was no spark. Instead, the whole activity felt soulless. Not only soulless but soul-crushing. I actively avoided playing instruments, not even looking at my guitar. It was much more rewarding to focus on my job, video games, anything but music. Not just making music but also listening to music. For some reason, I had developed resentment towards a former major source of joy.

Was this creative burnout? Didn’t I have every instrument I could dream of at my fingertips? What was holding me back? It took me more than two years to find out and to properly explain it, I first have to go into what productivity means in the context of leisure time.

Leisure Activities and Productivity

Does leisure time have to be productive? While it might seem like a question that we can safely answer with “Well, of course not! Leisure time is meant for relaxing and doing something fun!”, it is not that simple. Modern society has primed us to seek efficiency. This is incompatible with leisure.

Faith in “Technique”

French sociologist Jaques Ellul coined the term “technique” which is defined as “the totality of methods, rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity.”6 He makes the case that technique governs our lives in every aspect, as it is at the heart of the methods we choose to accomplish almost any task. We strive for optimization. Every process needs to be the fastest, cheapest; simply put: the best for a given situation. Technology (which should not be confused with technique) enables us to optimize more quickly and even automate tedious tasks, giving us more time to do more optimization. Ellul makes the case that since technique yields the most optimized way of going about our lives, we simply have no choice but to participate and buy into it. In “Jacques Ellul’s Technique in the Digital Age”, Paul D. Wilke summarizes our relationship with technique:

This is where our modern idea of progress stems. We just assume that every few years, our phones will be smarter, our internet faster, our weapons deadlier, and our lives better because they are so much more efficient. Technique always delivers and we assume it always will. That is our faith today. […] Technique is sinister because it is so persuasive and pervasive, so appealing to our inclination for comfort and ease; it appears to give much more than it takes, and in many ways that is true, but we are nonetheless trading freedom and spontaneity for security and comfort.

Technique’s promise is the enablement of progression. Without it, how can we reach the “next step”, a higher level of being, presumably with more comfort and fewer problems than we have now?

In a capitalist society, we have to believe in technique to win (or at least be a meaningful part of) the economic race we find ourselves in. Companies have to believe in technique to maximize shareholder profits. Employees have to believe in technique to outcompete adversaries in the job market. If any actor stops applying technique in their corporate life, others will happily fill that role, which, in the perceived zero-sum game we find ourselves in, will lead that actor to lose the game. Federal Reserve economist Eric R. Nielsen argues that these zero-sum games are rare in economics, arguing very much in the spirit of technique:7

Though the supply of some raw materials is limited, technological improvements are constantly increasing the productivity, distribution, and quality of the goods produced from these materials. These changes make virtually everyone better off. Thus, most economic activity cannot be called zero-sum games.

The idea is that instead of having a zero-sum game, we find ourselves in a rat race of “constantly increasing productivity”. The phrase “These changes make virtually everyone better off” also does a lot of heavy lifting here, which I cannot let go by uncommented. We live in a world of horrific economic inequality and I would argue that “constantly increasing productivity” is to blame. Maximizing economic processes comes down to the capital one can afford to allocate to it. Developing new technologies, improving infrastructure and investing in the workforce requires capital. Countries that have been historically starved of capital, due to theft, colonization, war or other factors, do not have the needed resources to effectively implement technique and are therefore left to be taken advantage of.

It becomes second (or even first?) nature for the modern human being to accept this fact as an unfortunate but necessary reality. From an early age, we learn to succumb to technique when first entering a school system. Adulthood handles us no kinder. We are left with no choice but to get in line and to optimize, maximize and incorporate technique into our daily lives. After all, we don’t want to be exploited. We want to be the exploiters, as far as our slowly eroding moral compass allows.

When Free Time Becomes Occupied

Ok, where was I? Uhhh.. oh yeah, this section was about leisure time. Let’s think about it: What does leisure time even mean in the context of technique? We structure our lives to optimize and maximize, mostly, but not exclusivly, in an economic context. To do so, we use personal planers and to-do apps to fully plan out our days. We use smartwatches to track our workout progress. We use services that summarize books and news articles to save time. We buy self-help books and books on how to be better at things. We read articles on the “Top 10 Ways To Improve” in whatever topic it is we want to improve. We completely obsess about personal progress to an outlandish degree.

What does this do to our perception of the little bit of free time we have?

It is obvious, isn’t it?

We have to maximize that time too and spend it to optimize ourselves!

One of the most batshit insane baffling opinion, I have ever read about free time and self-improvement, comes from the book “The Clean Coder: A Code of Conduct for Professional Programmers” by Robert C. Martin:8

You should plan on working 60 hours per week. The first 40 are for your employer. The remaining 20 are for you. During this remaining 20 hours you should be reading, practicing, learning and otherwise enhancing your career. […] I’m not talking about all your free time here. I’m talking about 20 extra hours per week. That’s roughly three hours per day. If you use your lunch hour to read, listen to podcasts on you commute, and spend 90 minutes per day learning a new language, you’ll have it all covered. […] Perhaps you don’t want to make that kind of commitment. That’s fine, but you should not think of yourself as a professional. Professionals spend time caring for their profession.9

That’s right.

You read that correctly.

Don’t call yourself a professional if you don’t spend the little leisure time you have on personal progress, specifically aimed at your career; oh sorry, it’s about the profession of course.

The sentiment is clear: Your job cannot just stay your job.

You have to let it seep into the rest of your life, otherwise you don’t deserve the title of “professional”.

It reads so bitter yet so revealing.

Martin’s opinion is the verbalization of technique with capitalist gatekeeping sprinkled in between.

The title of “professional” is used as a dangling carrot to entice the aspiring programmer to let technique inside their head.

To always strive to maximize time and to strive for optimization of the self.

While this might seem like an extreme example, you and I both know that technique implicitly forces us to do this to some degree. Modern life is filled with competition. We don’t have the time to not optimize leisure. Therefore, even activities we do for fun, need to have some kind of maximization attached to them. The reason for doing the activity is irrelevant, as long as its efficiency is analyzed, weak points are identified and quickly improved on. If you want to go hiking, you better get the best hiking gear on the market. If you like to visit art galleries, you better read up on the exhibited artists before you even attempt to inspect their artworks. If you go on vacation you better make sure that everything is in place so you can squeeze the most joy out of those days.

Maximum Leisure Efficiency

Don’t we feel bad when we are not productive? Isn’t there this nagging voice in the back of our heads that tells us to do something? When we have tasks we actually need to do and we are actively procrastinating, we usually don’t feel good. In Tim Urban’s TED talk on procrastination, he describes the mental space we occupy when procrastinating as the “dark playground” and summarizes it like so:

It’s when leisure activities are happening at times when leisure activities are not supposed to be happening. The fun you have in the “dark playground” isn’t actually fun, because it’s completely unearned and the air is filled with guilt, dread, anxiety, self-hatred – all those good procrastinator feelings.

This makes sense. After all, procrastination is linked with higher stress and poorer health. Subjective discomfort is part of procrastination as the artificial delay to starting (or finishing) a task is irrational which the procrastinator is aware of.10

However, does the equation change when leisure activities are happening at times when they are supposed to be happening? It would be rather unfortunate if we had similar thoughts about our free time then, wouldn’t it? Yeah, it would.

Too bad that’s the case. In a 2021 study, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures, Klaver and Lambrechts conducted a series of interviews with 10 participants, 9 of which between the age of 25 and 31, to study the effects of increased leisure time on the relationship between work and the “self”. While the interviews focus a lot on the lockdown itself and changes to living conditions concerning work, the most fascinating part of the interviews is about “wasting time”. I want to quote and comment on some excerpts of the paper, which I highly recommend you read (the names are pseudonymized):11

Throughout the interviews, the topics of “usefulness” and “productivity” recurred. Surprisingly, these topics were predominantly discussed by furloughed participants and not those working from home. Without work, most furloughed participants struggled with feelings of stress over how to spend this leisure time in a “productive” way. […] Ella experienced the pressure of having to “make something out of the day” for it not to be a “waste”. A good day during the lockdown was a productive day, and on bad days, negative thoughts about “unproductivity” would dominate. For Ella, a lack of structure and routine, usually provided by her job around which she structured her social and personal activities, felt overwhelming. Some days she felt optimistic, active, and motivated. On these days, she engaged in activities such as baking and reading, and savoured quality time with her partner. Other days presented a vicious cycle; the pressure of having to use time “wisely” was overwhelming, which then resulted in an “unproductive” day with “so much nothingness”. Eleonora shared a similar feeling of pressure to fill time as “too much free time is something [she did not] know how to handle”. She explained how work keeps “her mind busy” and distracted. This discussion suggests that we are so used to structure our lives around work that it forms part of our identity; we may not know what to do or who we are without it.

As modern human beings, we have been brought up in a world, that does not value our freedom, nor our time. It values capital. It values “the product”. It values work. Technique has shaped our collective willingness to submit to the idea that our worth is linked to how well we are able to maximize our efficiency, even in aspects of our life where efficiency is irrelevant. We hurt when we cannot achieve this. We feel guilt.

I need to ask you to recall the quote by Nielsen, about how increased productivity makes “virtually everyone better off”. Who is better off and in what sense? Are we better off when increased leisure time makes us feel guilty of “wasting” time and potential? How about Martin’s quote about the 60 hours of work, of which you owe 20 hours to yourself? Are we supposed to accept this debt and pay it?

Who profits from this thinking? We, as human beings, have found such a pervasive rationalization of our own existence that we now have a hard time to even comprehend who holds the keys to our prison. Instead of collaboratively searching for an exit and breaking out of this generational guilt, we start to fight amongst ourselves. Klaver and Lambrechts go on to summarize the interviews:

The interviews reflected how most participants experienced pressures of “productivity” during the lockdown. Moreover, pressures of “productivity” arose when participants compared themselves to those around them. For example, some participants believed they were “wasting” time because friends or family started an online course or decided to learn a new language, and they did not. Pressures of “productivity” can be linked back to Veblen’s idea of conspicuous consumption: a capitalist society puts so much value on leisure time, since it is so limited, that only those with an abundance of it can justify “wasting” it.

Enjoyment or entertainment is not something technique will be concerned with, except for industry’s purposes. More specifically, the entertainment industry’s purposes. In 1944, Adorno and Horkheimer wrote “The man with leisure has to accept what the culture manufacturers offer him.” and in modern times, culture manufacturers have become quite adept at providing us with the one thing our fatigued minds need to stay awake: the perception of a zero-sum game.

If my neighbor learns to master a new skill, has exposure to a new technology or has gathered insights that I have missed out on, will I fall behind? Will I not be presented with the same opportunities? Will I not be able to compete in the race to optimize? We suffer from a fear of missing out, that we have acquired through industrial indoctrination.

Likewise, if my neighbor has the ability to spend more on luxuries or amenities than me, does that mean my life is simply worse? In a 2003 study by Southerton, investigating the “time squeeze”, a general feeling of being harried in society, participants were interviewed to give “detailed discussions of the previous work and weekend day, as well as general observations of the time squeeze”. Some interviewees responded with anxiety about competition:12

In all cases pressures to ‘keep up’, to have a lifestyle or a standard of life comparable to those of others within one’s networks were identified as the fundamental sources of a ‘time squeeze’. Suzanne explained: “it is very much like everybody’s trying to get better than the other one – a better car or this sort of thing. . . . And that puts pressure on people to do more in their work or fit more into their life in general.”

This narrative also emphasized an expectation that lifestyle, or the accumulation of material goods, should always be on the rise throughout the life course. For example, Mary described how: “between friends, when one gets a new house you start to feel like you’re getting left behind, like you should have a three-bed by now or a car or, it’s like anything. At the moment everyone’s getting computers and we’re like, ‘should we get one’.”

This feeling of competition is fed into by a self-improvement and self-help industry that is ballooning and on a steady upclimb. This industry has put forth record-selling books with titles such as “Rich Dad, Poor Dad”. The obvious suggestion is clear. If you don’t buy these books, you will not get rich, your neighbor will. It is not surprising that self-help topic people mostly relate to are “Confidence”, “Motivation” and “Career”. Technique has left us to be empty shells playing a game of make-believe, with a fear of missing out on pretending to have confidence and motivation in a career we feel forced to pursue.13

What technique has not accounted for was the pandemic, which, all of a sudden, demonstrated that this game does not have to be played. This did not go unnoticed. In their paper, Klaver and Lambrechts conclude:

Among all participants, reduced pressures of “productivity” inspired an appreciation of “small pleasures” and increased appreciation of time for the “self”, creativity, and time to spend towards personal goals.

Reducing the pressure of “productivity”? That sounds like a plan!

Keyboard Epiphany

Back to music-making! My efforts to become more productive in my hobby did not just cause me to resent said hobby. It also caused me to feel guilty for not engaging in a thing that has the potential to enrich my life. Things had to change.

Monophonic Simplicity

The story of how I realized the problematic state of my relationship with my hobby is absurdly anti-climactic.

For some time now, I have been fascinated by Omnichords, electronic instruments mimicking Autoharps.

Their defining feature is that you can select a chord to play (without knowing how to play said chord) and then strum a melody (without knowing how to play in a fitting scale).

While these instruments do not literally play themselves, they lower the bar for a beginner (or drunk person) to play something musical and to experiment with sounds.

While browsing eBay I stumbled over an instrument: The Casio PT-30, a very early arranger-keyboard from the 80s. At first, it didn’t look special to me. Who cares about those old keyboards? They’re not even polyphonic! But taking a second look… Wait… What is that? Do you see that!?

What are those keys on the left? Are they?… No, it can’t be… They are chord selection keys! The PT-30 can play chords while you play a monophonic (one note at a time) line on the keyboard.14 While researching the sounds this little keyboard is capable of, I stumbled over a remarkable feature of the instrument. It has a built-in sequencer, meaning you can put in a melody at an arbitrary speed and then have the keyboard repeat it back to you. The PT-30 is in part a late spiritual successor to Scott’s “Circle Machine”! This in itself is not special as many keyboards have this feature. However, the PT-30 can harmonize your melody, meaning that it will try to play fitting chords to accompany you. The astute reader will realize, that’s the other way around from how the Omnichord works!

This sounded fascinating enough for me to pull the trigger. If you want to know more about this instrument you can read this old magazine article from “One Two Testing”.

I want to write a lot of positive things about this instrument. However, you must excuse me, my PT-30 is winking at me (since it permanently lives on my desk) and I want to play it… in order to gather my thoughts of course! I will just leave you with a quote from the “One Two Testing” article’s conclusion:15

Still that was for me one of the most attractive characteristics of the PT-30… that feeling that you’re always discovering new things to do with it and ingenious ways of overcoming problems and creating fresh music. That’s one of the definitions I use to distinguish a machine from a musical instrument. And the PT-30 qualifies as the latter.

Ok, I’m back. I have gathered my thoughts and here they are: The PT-30 is the most fun I had in a long time playing an instrument. Its slightly clicky, but dampened keys have incredibly short travel, making it very easy to play fast melodies without much pressure. Since there is no velocity-sensitivity, this works out fine. The pre-defined “chord instrument” has an artificial organ sound, which sounds strangely “complete” tone-wise. That’s also due to the built-in speaker which is, unsurprisingly, mid-focused but not as bad as one might think. What is surprising about the speaker is how loud it can get. You don’t need an amplifier for this keyboard when playing at home.

The PT-30 has 8 built-in sounds, of which I only find one or two usable. I mostly use the “horn” setting, since it is a nice mellow contrast to the brash organ sound and has a reasonable range. This is the intrinsic beauty of this instrument. There is no big choice to make. You can’t fiddle with parameters or obsess about automation like you can with software instruments. There is nothing to push you into overchoice. You are unable to not focus on your performance. And focus you must, since the chord buttons are somewhat strange to get used to at first, but once you play around with them for a few minutes, prototyping and exploring chord progression is as easy and simple as the rest of the instrument.

“Simple”. This word, too often used in negative contexts, has, after all my experimentation with music gear and software, become especially important to me. Simplicity is paradoxically effective. Having less choice is incredibly freeing when trying to create something. It helps to focus and to get into a certain flow state while playing an instrument or developing ideas.

While writing this post, Cameron from the YouTube channel “Venus Theory” uploaded a video on simplicity and restrictions in creative work. It goes deeper into the topic than I care to, so I can happily recommend it.

So, what about the harmonization feature of the keyboard? It’s finicky, sensitive and doesn’t always work, but when it works… It’s magical. Programming the sequencer and getting back a harmonization feels much more like a conversation than anything else. I formulate my request, which is somewhat complicated and requires a few steps. Then, there is a short pause, giving the microcontroller inside the keyboard time to compute the chords. After its respite, the keyboard answers. When it misunderstands me I ask it to rephrase, which it does. I change up the melody in hopes that other chords will be inferred. And they are. The musical notes I play, a highly emotional language to me, are received by this little inanimate object and, more importantly, answered. This keyboard speaks my language. It doesn’t always understand me, but we communicate and that is all that matters.

Digital Rut, Begone!

I was so obsessed with productivity in my hobby that I eschewed the magic that I now feel with the PT-30. My primary instrument is the guitar and guitars, especially acoustic guitars, are incredibly simple (there is that word again). There is no automation. The guitar will not play itself. It will also not resist being played. The player is in charge.

Stringed instruments have wonderful physicality to them. You can strum, pluck, bow and slap strings. You can use your fingers or you can use picks. What material should those picks be made out of; Fantastic plastic? Wonderous wood? Or just plain metal? Whatever your choice is, you can be sure that your guitar will react to it. The feel of playing changes as if the guitar first has to get used to the new material. Its sound equally changing timbre. A wonderful symbiosis of player and instrument arises.

A 2013 study by Simoens and Tervaniemi found that musicians who identify strongly with their instrument have less anxiety before, during and after rehearsals and performances.16 These musicians have such a deep relationship with their instrument (or voice) that they feel that “there is no difference between” them. Of the, mostly classical, musicians who participated in the study, over 50% reported having such a special relationship. The study’s authors find that these musicians generally have better professional well-being than their colleagues with a less intense connection to their instruments.

I am not a classical musician and therefore, I don’t really know how closely my experience relates to the study, but I cannot ignore the feeling that I do understand what they are talking about. Feeling an instrument becoming an extension of yourself, feeling the comfort it brings you, like coming home to a heated room and warm shower after a cold and hard day. The feeling that the instrument merges with you, its voice becoming your voice and in the end, it speaking your language. My guitar gives me that feeling.

Digital instruments, however, do not. It’s quite the opposite. In the study by Simoens and Tervaniemi some musicians reported that their instrument was an “obstacle to overcome” between them and the audience. These musicians generally had much higher perceived stress than their peers. Digital instruments feel like this to me. It does not matter, whether I am playing a MIDI keyboard, which obviously is a physical instrument. I need to feel a connection to an instrument and the skeuomorphic user interfaces on my computer screen aren’t something I can have a connection with.

There are enough sources out there that will praise digital music-making. One of the major advantages being highlighted is convenience and I understand that. If I were a professional producer with a productivity goal, I would use a digital folk-band recreation too! But, let’s be honest here. Where is the love in making music when you have to replace actual musicians with minutely programmed fake performances? Where is the joy of dealing with little intricacies of performers or instruments in creative ways?

I also can’t overlook the massive amounts of advertisements for “AI-powered” creative tools, the newest and biggest perversion of “faking it”. It evokes this dreadful feeling, that we, as creatives, are so utterly consumed by the need for convenience that we will literally outsource creative work to a machine. How utterly horrible.

I am aware that not everybody thinks like that. Many people feel perfectly fine using software in their music production. They feel the joy, they feel the muse, they feel a connection to the music they make. All of that is fine. It just wasn’t fine for me. It cheapened my experience and I am not sad about leaving it behind.

My hobby is fun again. I now realize that I need to focus on what feels right, not what I can rationally explain. I don’t need to feel guilty when I don’t spend my time recording new demos or songs. It’s totally fine to just play a few silly melodies on an instrument of choice and be done with it. Nobody can judge my efforts but myself and I have decided to stop judging and focus on what counts: The joy of the creative process.

Conclusion

So, how can I conclude this post? I have written about automation possibilities in music-making and how my obsession with productivity has led me to use this automation to such an extent that I lost touch with my favorite hobby. Furthermore, I have covered the motivation behind this “maximization” thinking, which is rooted in our societal obsession with “not wasting time”. Lastly, I have discussed how a Casio keyboard from the 80s broke me out of this rut and how important a connection to an instrument is to me.

What do we make out of this? Personally, I have learned a lesson and I have learned it the hard way. Not only was I stressing about making music. Even writing this blog stressed me out at some point. I have quite a few drafts I am working on and for some time I felt bad looking at the pile of unfinished work. Why can’t I work quicker? Why can’t this stuff be done already?

Letting this feeling go is hard to do. It involves reevaluating the things that are actually, not superficially, important to oneself and rethinking what it means to waste time. What do we want to achieve with the resources we have? How do we assess the value of the things we do and how do we want to live our life? It is incredibly hard to find satisfying answers to these questions.

It is hard because we are still living in a world that requires us to be productive members of society (whatever that means). For the most part, it not only entails doing work but comparing your performance to the performance of other people. To not care means to disengage. It means letting the world outside do its business and also, letting a part of social life go by. A bad part of social life. It is only fitting to close this blog post with a quote by “India”, a participant in the study by Klaver and Lambrechts:11

“I think it was really enlightening to question what productivity means and how all of us, engaging in society, Western society, have just been programmed to see life as this, from A to B, from doing to doing, and from learning to learning, and we measure ourselves by what we achieve [ . . . ] but we are also something without doing all those things, without a job or without another degree, or without a promotion.”

-

The album turns 10 years old on April 1, 2024! ↩︎

-

Irwin Chusid, Jeff Winner and Piet Schreuders, “Raymond Scott: Artifacts from the Archives”, page 90-93 ↩︎

-

Irwin Chusid and Jeff Winner, “Circle Machines and Sequencers: The Untold History of Raymond Scott’s Electronica”, 2016 ↩︎

-

I can recommend the “Manhattan Research, Inc.” compilation album to get a sense of what he was capable of composing using his inventions. ↩︎

-

The term “in the box” comes from the music production scene and describes keeping your production pipeline inside your computer, instead of mixing with “outboard gear”. ↩︎

-

The quote and more information on the term can be found here. Recommended reading: “The Technological Society” by Jaques Ellul; ISBN-13: 978-0394703909 ↩︎

-

“Jargon alert : Zero-sum game,” Econ Focus, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Eric R. Nielsen, 2005 ↩︎

-

“The Clean Coder: A Code of Conduct for Professional Programmers” by Robert C. Martin; ISBN-13: 978-0137081073 ↩︎

-

K. B. Klingsieck, “Procrastination,” European Psychologist, vol. 18, no. 1. Hogrefe Publishing Group, pp. 24–34, Jan. 2013. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000138. ↩︎

-

J. S. Klaver and W. Lambrechts, “The Pandemic of Productivity: A Narrative Inquiry into the Value of Leisure Time,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 11. MDPI AG, p. 6271, Jun. 01, 2021. doi: 10.3390/su13116271. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

D. Southerton, “`Squeezing Time’,” Time & Society, vol. 12, no. 1. SAGE Publications, pp. 5–25, Mar. 2003. doi: 10.1177/0961463x03012001001. ↩︎

-

This has spawned an onslaught of grifters, promising people an easy way to escape this game using “passive income” and get-rich-quick schemes. Tom Nicholas has created an entertaining video essay on this topic. ↩︎

-

There is a whole type of instrument that has this feature: the chord organ. An early example of such an instrument is the tube-based Hammond S6. ↩︎

-

Sadly, it’s unknown to me who the author of this article is, which is a shame because I love their writing style! ↩︎

-

V. L. Simoens and M. Tervaniemi, “Musician–instrument relationship as a candidate index for professional well-being in musicians.,” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, vol. 7, no. 2. American Psychological Association (APA), pp. 171–180, May 2013. doi: 10.1037/a0030164. ↩︎